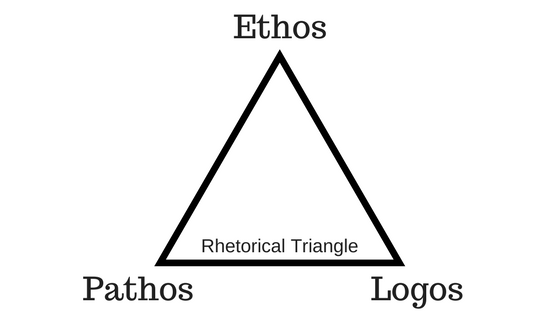

Ethos, pathos, and logos are three modes of persuasion identified by Aristotle. By appealing to these three elements, a speaker or writer will increase her chances of persuading an audience.

Ethos is an appeal to the writer's credibility and character.

Pathos is an appeal to the emotions of the audience.

Logos is an appeal to logic and reason.

See below for a more detailed look at how writers or speaks appeal to these important elements of persuasion.

Understanding Appeals to Ethos

When you evaluate an appeal to ethos, you examine how successfully a speaker or writer establishes authority or credibility with her intended audience. You are asking yourself what elements of the essay or speech would cause an audience to feel that the author is (or is not) trustworthy, credible, and of high moral character.

A good speaker or writer leads the audience to feel comfortable with her knowledge of a topic. The audience sees her as someone worth listening to—a clear or insightful thinker, or at least someone who is well-informed and genuinely interested in the topic.

Some of the questions you can ask yourself as you evaluate an author’s ethos may include the following:

- Has the writer or speaker cited her sources or in some way made it possible for the audience to access further information on the issue?

- Does she demonstrate familiarity with different opinions and perspectives?

- Does she provide complete and accurate information about the issue?

- Does she use the evidence fairly? Does she avoid selective use of evidence or other types of manipulation of data?

- Does she speak respectfully about people who may have opinions and perspectives different from her own?

- Does she use unbiased language?

- Does she avoid excessive reliance on emotional appeals?

- Does she accurately convey the positions of people with whom she disagrees?

- Does she acknowledge that an issue may be complex or multifaceted?

- Does her education or experience give her credibility as someone who should be listened to on this issue?

Some of the above questions may strike you as relevant to an evaluation of logos as well as ethos—questions about the completeness and accuracy of information and whether it is used fairly. In fact, illogical thinking and the misuse of evidence may lead an audience to draw conclusions not only about the person making the argument but also about the logic of an argument.

Recognizing a Manipulative Appeal to Ethos - Examples

In a perfect world, everyone would tell the truth and we could depend upon the credibility of speakers and authors.

Unfortunately, that's not always the case.

You would expect that news reporters would be objective and tell new stories based upon the facts. But Janet Cooke, Stephen Glass, Jayson Blair, and Brian Williams all lost their jobs for plagiarizing or fabricated part of their news stories. Janet Cooke’s Pulitzer Prize was revoked after it was discovered that she made up “Jimmy,” an eight-year old heroin addict (Prince, 2010). Brian Williams was fired as anchor of the NBC Nightly News for exaggerating his role in the Iraq War.

Others have become infamous for claiming academic degrees that they didn’t earn as in the case of Marilee Jones. At the time of discovery, she was Dean of Admissions at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). After 28 years of employment, it was determined that she never graduated from college (Lewin, 2007). However, on her website (http://www.marileejones.com) she is still promoting herself as “a sought after speaker, consultant and author” (para. 1) and “one of the nation’s most experienced College Admissions Deans” (para. 2).

Beyond lying about their own credentials, authors may employ a number of tricks or fallacies to lure you to their point of view. When you recognize fallacies being committed you should question the credibility of the speaker and the legitimacy of the argument. If you use these when making your own arguments, be aware that they may undermine or destroy your credibility.

Understanding Appeals to Pathos

People may be uninterested in an issue unless they can find a personal connection to it, so a communicator may try to connect to her audience by evoking emotions or by suggesting that author and audience share attitudes, beliefs, and values—in other words, by making an appeal to pathos.

Even in formal writing, such as academic books or journals, an author often will try to present an issue in such a way as to connect to the feelings or attitudes of his audience, to provoke an emotional response favorable to his writing purpose.

When you evaluate pathos, you are asking whether a speech or essay arouses the audience’s interest and sympathy. You are looking for the elements of the essay or speech that might cause the audience to feel (or not feel) an emotional connection to the content.

An author may use an audience’s attitudes, beliefs, or values as a kind of foundation for his argument—a layer that the writer knows is already in place at the outset of the argument. So one of the questions you can ask yourself as you evaluate an author’s use of pathos is whether there are points at which the writer or speaker makes statements assuming that the audience shares his feelings or attitudes. For example, in an argument about the First Amendment, does the author write as if he takes it for granted that his audience is religious?

Recognizing a Manipulative Appeal to Pathos - Examples

Up to a certain point, an appeal to pathos can be a legitimate part of an argument. For example, a writer or speaker may begin with an anecdote showing the effect of a law on an individual. This anecdote will be a means of gaining an audience’s attention for an argument in which she uses evidence and reason to present her full case as to why the law should/should not be repealed or amended. In such a context, engaging the emotions, values, or beliefs of the audience is a legitimate tool whose effective use should lead you to give the author high marks.

An appropriate appeal to pathos is different than trying to unfairly play upon the audience’s feelings and emotions through fallacious, misleading, or excessively emotional appeals. Such a manipulative use of pathos may alienate the audience or cause them to “tune out”.

An example would be the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) commercials featuring the song “In the Arms on an Angel” and footage of abused animals. Even Sarah McLachlan, the singer and spokesperson featured in the commercials admits that she changes the channel because they are too depressing (Brekke, 2014).

Even if an appeal to pathos is not manipulative, such an appeal should complement rather than replace reason and evidence-based argument. In addition to making use of pathos, the author must establish her credibility (ethos) and must supply reasons and evidence (logos) in support of her position. An author who essentially replaces logos and ethos with pathos alone should be given low marks.

Understanding Appeals to Logos

When you evaluate an appeal to logos, you consider how logical the argument is and how well-supported it is in terms of evidence. You are asking yourself what elements of the essay or speech would cause an audience to believe that the argument is (or is not) logical and supported by appropriate evidence.

To evaluate whether the evidence is appropriate, apply the STAR criteria: how Sufficient, Typical, Accurate, and Relevant is the evidence?

Recognizing a Manipulative Appeal to Logos - Examples

Diagramming the argument can help you determine if an appeal to logos is manipulative. Are the premises true? Does the conclusion follow logically from the premises? Is there sufficient, typical, accurate, and relevant evidence to support inductive reasoning? Is the speaker or author attempting to divert your attention from the real issues? These are some of the elements you might consider while evaluating an argument for the use of logos.

Pay particular attention to numbers, statistics, findings, and quotes used to support an argument. Be critical of the source and do your own investigation of the “facts.” Maybe you’ve heard or read that half of all marriages in America will end in divorce. It is so often discussed that we assume it must be true. Careful research will show that the original marriage study was flawed, and divorce rates in America have steadily declined since 1985 (Peck, 1993). If there is no scientific evidence, why do we continue to believe it? Part of the reason might be that it supports our idea of the dissolution of the American family.

License and Attribution